It is truly remarkable to see how Arduino, the easy-to-use hardware and software platform aimed to create a world where there are no barriers to technology and innovation, has revolutionized the sector of electronics by democratizing it for students, innovators, and generally curious people. But of course, it was not an overnight success. Massimo Banzi talked to us about the innovation of Arduino and the first years of the company, the creation and the philosophy behind the FabLabs, as well as how making all the mistakes possible as an entrepreneur can lead to becoming a great mentor.

Looking back at your academic background and early experiences, what first sparked your passion for electronics design and innovation?

“Well, I can trace the part of me that led to electronics and design to a toy I got as a present as a 7-year-old. It was system called ‘Lectron’ originally made by Braun, a German company that was kind of like the Apple of the 60s. With Lectron, you could build circuits using small magnetic blocks and as a matter of fact, it was partially designed by Dieter Rams, the designer who inspired much of Apple’s design over the past 20 years. So, at the age of seven, I got this as a toy, and I got into electronics and design at the same time.”

What sparked the idea for Arduino and what do you remember most from the early months?

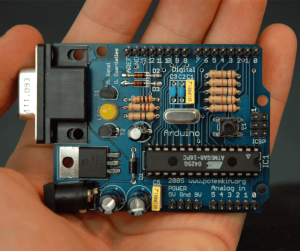

“Arduino, being a piece of electronics, has a strange origin because it was born in a design university. Normally you can see these kinds of products are born out of engineering school. The objective was to the help the students quickly go from an idea to a working prototype, with the least amount of background knowledge necessary. It probably took two and a half years to get to the ‘Arduino’ you know and produce the first boards that still look like the current Arduino.”

How would you describe the atmosphere in those first months of building the Arduino team?

“The first months of Arduino were very exciting: the team was made of people from different parts of the world, with friends joining from the USA and Sweden. We brought them to Ivrea, a place with long tradition in manufacturing electronics because of the Olivetti company. I was constantly rushing through manufacturers to get things made. It was a period full of intense interaction with a group of people that contributed a lot and this is what made that time special.”

You helped launch Italy’s First FabLab. How do you view the role of FabLabs and maker communities today in shaping Europe’s innovation landscape?

“As the founder of the first FabLab in Italy, I saw the whole curve and I think it follows a little bit the Gartner hype cycle. About 10 years ago, when there was a huge hype, and even villages with like 3000 people were opening a FabLab which didn’t make any sense because of what they didn’t do since they weren’t building a community before building a FabLab.

The first FabLab started this way. We had already built a community in Torino, and then came the moment when we thought, “Let’s find a place for this community.” Now that the hype has died down, the groups who survived are the ones actually creating innovation and bringing together people from different backgrounds. For example, FabLab Torino was bringing together designers, architects, engineers, software people, and in general, random people from the town. Looking back, I think we had to go through that hype curve, because now FabLabs are makerspaces with a real role.”

Tech Europe Foundation’s mission is to bridge scientific excellence and deep tech entrepreneurship. From your own journey, what lessons would you share with young founders seeking to turn ideas into real world impact?

“One thing that I have noticed is that there is a lot of hype and a narrative around startups that originates from Silicon Valley. And people in Europe tend follow that narrative which is, honestly, quite misleading. Don’t believe the hype of this narrative. What you need to do instead is that if you are doing deep tech in Europe, take advantage of Europe, take advantage of the specific values of Europe. Every overnight success that you find in startups was always preceded by years of people working extremely hard.”

Why is the CDL approach unique and why should founders consider joining the program?

“I’m very fascinated by the CDL program because it’s spread across the world in different locations, and every location is focused on a certain type of industries, which is very smart. Sometimes people try to work on every single technology on the market, but specificity is great. My advice to the founders is to try to take advantage of the experience and capabilities of each city or location. I like this model because, as a founder, you get a network where each location represents a specific sector. I think that’s much better than trying to be everything everywhere.”

What does being a CDL mentor mean to you personally and what inspired you to take on that role?

“When I help startups, my pitch is simple: I have made every single mistake that a person can do while making a company. I’ve done them all. At least if we work together, one of the things I can offer is a moment of pause where I can say “Wait a second, I have been through this, and it didn’t work out really well”.

We need companies. I don’t fully like the word “startup” because it’s tied to a misleading narrative. What I appreciate are people who want to be entrepreneurs and create companies because they create innovation, jobs, and advance the society. Applying my past mistakes to help young founders is my way of supporting that, and I think that’s my role now.”